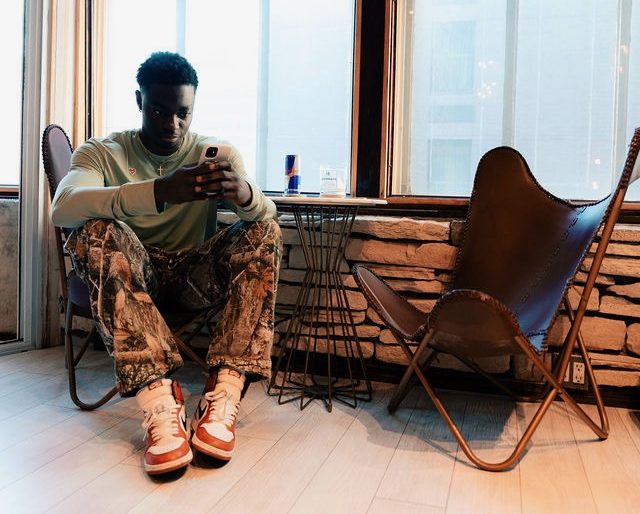

Athlete. Artist. Engineer.

Jaeschel Acheampong doesn’t restrict himself to one label. He chooses to define himself by all of the above.

As a former track athlete who starred as a long jumper and now works as an engineer while chasing his creative dreams, Jaeschel is a model for defying limits.

These are Jaeschel’s lessons from devoting himself to “AOTA” (all of the above).

You Don’t Have to Just Choose One

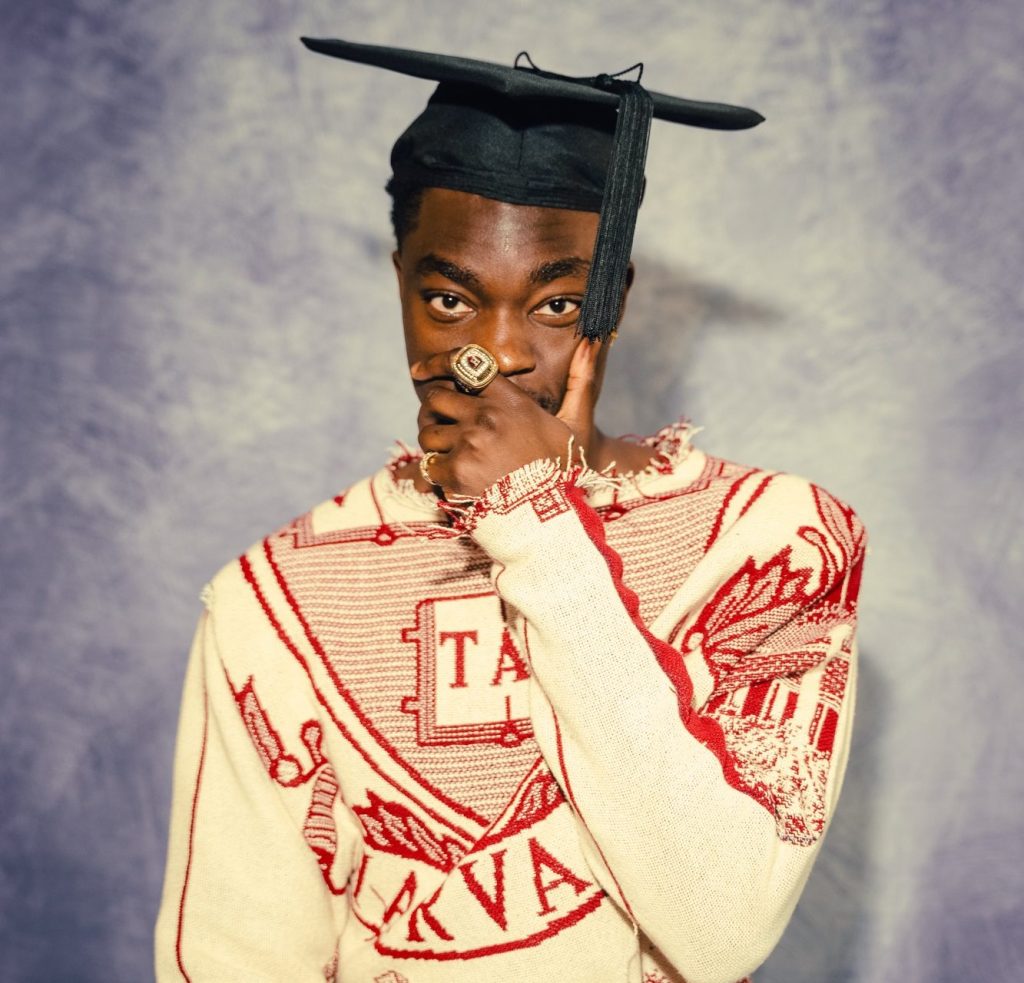

In high school, Jaeschel was told that his rap music and student-athlete ambitions could not coexist. The music he was making didn’t fit the mold of a Harvard student.

So he wiped his streaming options off the internet. But then something funny happened. At his Harvard interview, over half of the conversation was about how he produced music.

In college, instead of letting his music dreams die, Jaeschel chose to intersect them with his life as a student-athlete. He shared, “I wouldn’t allow myself to be an athlete there and not this person here.”

Wearing different hats didn’t mean letting his other priorities suffer. It meant doing them all at a high level and not letting limits stop him. He explained, “There are certain times when you can take on too many things at once or bite off more than you can chew, but I would rather want to find that out than have someone tell me that I can’t.”

This meant earning a rigorous degree, exhausting himself on the track, and pursuing art. All at once.

He credits his coaches for helping him balance his passions. His high school coach, Coach Swisher, encouraged him to take more time to focus on beats in the summer, so he could shift his greater focus to track when it was time to train. Similarly, on days when Jaeschel had a DJ gig at night, his Harvard coach, Coach Mangiacotti would tell him, “If you can, come to practice three hours earlier so that you have time to practice [djing] before you have this set.”

The people around him allowed him “to fan all those flames at once.” But it was Jaeschel who devoted the time and effort, while never losing sight of who he was wholly.

The One at a Time Mindset

“The beauty of long jump is that you kind of know exactly how many jumps you’ve got every single time,” Jaeschel shared. “You are guaranteed three jumps and three jumps only.”

One of Jaeschel’s biggest hurdles was overcoming forward-thinking on the track. He had to adopt the “one at a time” mentality that his coach instilled in him.

Which was even more difficult given the unique nature of long jump, as unlike running events, “You can’t line up next to someone and know that like right now I’m in third place,” Jaeschel explained. “In long jump, if someone just broke the school record, everyone’s yelling. Therefore, right before you line up, you have to focus on that,” he added.

He had to shut the outside noise out. He said he had to learn that, “I can only control this jump that I’ve laced up for.”

He explained one of his methods, “I always have my headphones in purely because I need to lock in on just what I’m doing at the time, because the moment other things start to fly into my head, problems happen.”

The mentality became even more important with bigger stakes, as Jaeschel explained, “The more competitive the track meets are—like nationals, regionals, all those things—you can’t bring your headphones. You can’t hear your coach. You can’t have those things.”

He continued, “Therefore, I had to try and recreate these moments where my heart is racing, where I’m thinking about other things and trying to narrow my focus.”

His solution? Ice baths.

Recreating the 20-minute three-jump series at meets, Jaeschel trained his mental state for the moment with sets of two 10-minute ice baths. He expressed, “When you’re in the ice bath, your brain is screaming, racing, thinking about a bajillion things, right? And what I would try to do is make sure I was able to count to a hundred. If I messed up, I’d have to restart.”

It worked by sending his body into shock, as he shared, “My entire body is screaming; everything in my body is shaking. I can’t control the nerves or the excitement that I have when I compete. But I can control narrowing my focus. So I would literally sit in there…it started to work flawlessly.”

Jaeschel taught himself to block out the noise and focus so well that when he jumped over 25 feet, a feat earning him 2nd all-time in the Harvard indoor track record books, he didn’t even realize what he had done. It had felt like just another jump to him…until the crowd erupted.

This practice carried over into other aspects of his life too: “This is even to the way I take exams, even to the way that I produce… [I] try and replicate the exact environment that I’m going to be in.”

To feel comfortable for exams, Jaeschel explained, “I would take practice exams in the exact seat that I’m sitting in for that exam because… [it] allows me to be like ‘I’ve done this before. So it’s not like I’m doing anything new anymore.’”

No matter the area of his life, Jaeschel recreated the moments so when it was time for the bigger stage, he’d been there before. Come meet day, it was just the same Jaeschel that had done the same thing over and over again.

Sometimes Breaks are Necessary

Along the way, Jaeschel learned that sometimes breaks are necessary—or even forced.

Throughout his career, he was “injured consistently,” but usually, that just meant taping him up, taking an ibuprofen, and competing anyway. He remembered, “I wouldn’t allow myself to slow down. I wouldn’t allow myself to take breaks.”

Ultimately, Jaeschel was forced to take a break when a herniated disc left his back like “scrambled eggs,” and he re-tore his hamstring in his senior year. Leading up to then, he spent years trying to take on more and more, and by his junior year, he started to figure it out. But as he recalled, “Even though I figured it out, I tried to add more, and that more is what made me realize: hey, sometimes you need to take that break. Don’t wait until life gives you a break.”

The perfect balance is hard to find, and he’s always adding more to his plate when he can. The willingness to add more is a big part of what makes Jaeschel so special, but sometimes the skill is in taking a step back.

The Power of Surrounding Ambition

At Harvard, Jaeschel was surrounded by success. His peers helped drive success. But the off-the-field success posed some challenges as a captain.

With a range consisting of some teammates building fortune 500 companies to others qualifying for the Olympics, as a captain, he recognized everyone’s track focus differed.

So he didn’t ask his teammates to all put forth the same effort. He shared, “I felt like what was fair for me to ask for people was that if you have decided that track is going to take up 60% of your life, when you come to that track, empty out that 60%.”

Jaeschel might’ve been sidelined with an injury, but he was there to push his teammates from the bikes. He remembered his mentality, “If you have put down: this is how far I want to run, or this is how heavy I want to lift… I will do everything in my power as a captain to make sure you empty that battery, empty that tank to make sure that we’re getting there.”

He enforced this mindset because “it translates across whatever you have set your mind to do.” Whether it’s sport, business, or art, Jaeschel’s mantra stands: empty that battery.

Being around ambitious peers meant seeing firsthand that there are no excuses to be made. He remembered at the Ivy League Heptagonal Championships, “Everybody there was at an Ivy League school, trying to get an Ivy League degree, trying to do these Ivy League, hard internships. And all of us are in this place. There are 600 of us and we’re all here to compete… it never gave me an excuse.”

He added, “You would see people cook you in a race and then turn around and get an internship at JP Morgan. I would say the higher performer you were on the track, the higher performer you were everywhere else.”

Sharing a World of Choice

Inspired by his father’s move to the United States from Ghana and ambitions to build a hospital there, Jaeschel is willing to take his own risk by chasing his dream.

Whether he reaches it or not, to him, it’s about giving the effort to have a chance. Jaeschel shared, “I had really wanted to run pro track, but my body kept getting hurt, and I couldn’t; I wasn’t able to check those boxes. But part of the reason why I don’t beat myself up for it is because I also want to perform at Coachella…if I get hurt, if I fail, if I do these things, I know that I legitimately tried my hardest, and I can’t be mad if God didn’t write that in my cards for me.”

He expressed inspiration that his dad just gave him, “My dad told me this yesterday: you might reach a Coachella that isn’t the Coachella you’re thinking about. Instead of you performing that Coachella, [maybe] you have a whole creative agency in Paris.”

Whether success comes in the way Jaeschel is picturing right now or in another form, what matters to him is giving it 100%.

Giving 100% effort is what separated him in track. He remembered, “I was able to compete in two meets [as a senior]… the reason why it wasn’t even a question [to my coach], ‘Is Jaeschel traveling with us or not,’ is because my coach was certain that if I could, I’m going 100%. There are people that you might not see that.”

Jaeschel’s song Chance to Live expresses this mindset, as he said, “That song was actually commissioned for Heartbreak [Hill], a running company. And their entire thing is: run hard, risk heartbreak. By trying something really hard, you’re risking the potential to fail. And I’m okay with that.”

Jaeschel shared that his creative aspirations are to “be an inspiration to the next generation of creative youth.” He said: “There’s this world that our parents want us to live in, right? Go to a good school; get this good job—especially being Africans, part of the thing is lawyer, doctor, engineer, and that’s it—but the world that I’m trying to curate is that, that isn’t just it.”

He wants to inspire kids to pursue a world with their passions, as he emphasizes, “You don’t have to be a streamer or an engineer. You don’t have to be a doctor or an artist. You can do both.”

Reflecting on the world he once thought he was restricted to, he mentioned, “I wish that there was a world where 17-year-old Jaeschel could see that there are all these people who are doing both. So you don’t have to do that.”

Jaeschel explained that success across different areas“I am able to do the things that I’m able to do, [and] I see the people who are able to accomplish these things, and it’s because they don’t allow one sector of their life to be shut out from the rest. They pull influences from there… by intersecting different cultures, different themes, different lessons, different aspects about yourself, that is where you get to be the best, most purest, most accurate version of you.”

His journey is a powerful message to the next generation: the choice is yours. Don’t restrict yourself to just one of your passions; allow them to intersect, and empty your battery to your fullest capabilities in each.

Jaeschel Acheampong is living proof that the only limit you have is the one you accept.

Leave a comment